Nobel Prize Winners from Hungary

Who are the Nobel Prize winners researchers who are connected to Hungary by Hungarian birth or Hungarian origin? György Bazsa, Doctor of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and Professor Emeritus of the University of Debrecen, seeks to answer this question in his article. The aim of his compilation was to provide an overview of the important information available on the subject.

“The question of national affiliation can be quite complicated in a multi-ethnic country such as the Kingdom of Hungary within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, where marriages between people of different nationalities were common. The name of the country itself also depends on the historical context, as Hungary’s borders changed dramatically over the course of the 20th century as a result of the Treaty of Trianon (1920), the Vienna Awards (1938 and 1940) and the Paris Peace Treaty (1947); there were areas that belonged to the motherland at one time and to its neighbours at another. In many of these regions, members of multiple nationalities lived together and often intermarried. As a result, several Nobel Prize winners (and, of course, other scientists) are today claimed by more than one country and nation as their own.”

(Excerpt from an article by György Bazsa in the journal Magyar Tudomány (Hungarian Science). Click here to read the full article in Hungarian.)

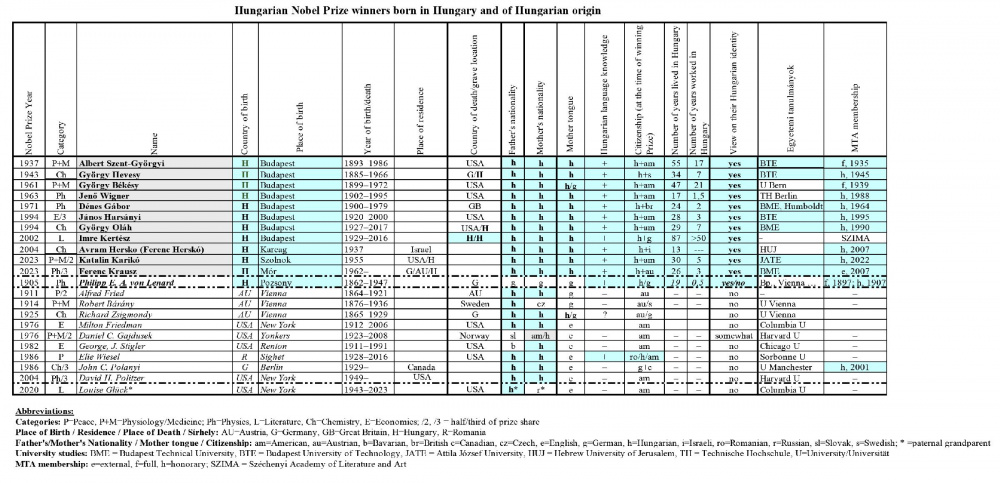

Summary table of Hungarian Nobel Prize winners born in Hungary and of Hungarian origin (Click on the image to enlarge the table.)

Summary table of Hungarian Nobel Prize winners born in Hungary and of Hungarian origin (Click on the image to enlarge the table.)Hungarian and Hungarian-Born Nobel Laureates

All of the following had/have Hungarian parents and citizenship, and their mother tongue was Hungarian. They all were born, educated and lived in Hungary for decades. All of them are (were) members of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

The names in bold below link to the nobel.se webpage.

Photo: wimimédia commons

Photo: wimimédia commonsAlbert Szent-Györgyi

(Budapest, 1893 – Woods Hole, MA, USA, 1986) – Hungarian doctor and biochemist

1937 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for his discoveries concerning biological combustion processes, with special emphasis on vitamin C and the catalysis of fumaric acid”.

Parents: Miklós Szent-Györgyi and Jozefina Lenhossék.

After completing his studies at Lónyay Calvinist Secondary School, Szent-Györgyi earned a degree as a medical doctor from the University of Budapest, and then earned a PhD at the University of Cambridge. He was then a professor at the Ferenc József University in Szeged from 1928–1945, during which time he served as rector of the then Horthy Miklós University from 1940-1941. He was also active in the Hungarian resistance during World War II and entered Hungarian politics after the war. He was elected to Parliament and helped re-establish the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. In 1947, the political changes in Hungary led Szent-Györgyi to move to Woods Hole in the United States, where he founded the Institute for Muscle Research at the Marine Biology Laboratory. He is credited with first isolating vitamin C and discovering many of the components and reactions of the citric acid cycle and the molecular basis of muscle contraction.

Szent-Györgyi died in Woods Hole and is buried there.

Photo: wikimedia commons

Photo: wikimedia commonsGyörgy Hevesy

(Budapest, 1885 – Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany, 1966) – Hungarian radiochemist.

1943 Nobel Prize in Chemistry “for his work on the use of isotopes as tracers in the study of chemical processes”.

Parents: Lajos Hevesy-Bischitz and Eugenia Schossberg-Tornyai.

Hevesy studied at Piarist Secondary School in Budapest, then at universities in Budapest and Berlin, and then earned his PhD in Physics at the University of Freiburg. He became a professor of physical chemistry at the University of Budapest, but in 1920 he moved to Copenhagen, where, in 1922, he discovered (with Dirk Coster) the element hafnium. He is the father of the isotope tracer principle. By 1943, Copenhagen was no longer a safe place for a Jewish scientist, so Hevesy fled to Sweden, where he worked at Stockholm University until 1961. It was here he began to use radioactive isotopes to study plant and animal metabolism. Hevesy developed the X-ray fluorescence analysis method and discovered the alpha radiation emitted by samarium. He received the Atoms for Peace Award in 1958 for his contributions to the peaceful application of radioactive isotopes.

Hevesy died and was buried in Freiburg. In 2001, at the request of the family, his ashes were moved to the Fiumei Road Cemetery in Budapest.

Fotó: Wikimedia Commons

Fotó: Wikimedia CommonsGyörgy Békésy

(Budapest, 1899 – Honolulu, HI, USA, 1972) – Hungarian-American biophysicist

1961 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for his discoveries of the physical mechanism of stimulation within the cochlea”.

Parents: Sándor Békésy and Paula Mazaly.

Békésy completed his secondary school studies in Constantinople, Budapest and Zurich, and his university studies in Budapest, Munich, Zurich and Bern. Using stroboscopic photography and a silver powder marker, he was able to observe that the basilar membrane moves as a surface wave in response to sound and that high frequencies produce greater vibration at the base of the cochlea, while low frequencies create more vibration at the apex. Békésy concluded that his observations demonstrated how different sound wave frequencies are locally dispersed before exciting different nerve fibers that lead from the cochlea to the brain. Between 1923 and 1946, he was employed by the Royal Hungarian Post Office, and from 1947-1966 he worked at Harvard University. After his laboratory was destroyed by fire in 1965, he was invited to lead a sensory sciences research laboratory in Honolulu. He became a professor at the University of Hawaii in 1966 and died in Honolulu.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Wikimedia CommonsJenő Wigner

(Budapest, 1902 – Princeton, NJ, USA, 1995) – Hungarian-American theoretical physicist

1963 Nobel Prize in Physics (shared with Maria Goeppert Maye and J. Hans D. Jensen) “for his contributions to the theory of the atomic nucleus and the elementary particles, particularly through the discovery and application of fundamental symmetry principles”.

Parents: Antal Wigner and Erzsébet Einhorn.

Wigner graduated from the Fasori Lutheran Secondary School in Budapest, and then graduated form the Technical College of Berlin in 1922 and received his PhD in 1925. From 1937, he was a professor at Princeton University. He worked as an assistant at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin and with David Hilbert at the University of Göttingen. Wigner and Hermann Weyl were responsible for introducing group theory, in particular symmetry theory, into physics. He also did pioneering work in pure mathematics. Wigner’s theorem is the cornerstone of the mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics. He is also known for his research into the structure of the atomic nucleus. In 1930, Wigner was hired by Princeton University, together with János Neumann, and moved to the United States, where he became a citizen in 1937. During the Manhattan Project, Wigner’s team was tasked with designing production nuclear reactors that would convert uranium into weapons-grade plutonium. Wigner and Leonard Eisenbud developed an important general approach to nuclear reactions, the Wigner-Eisenbud R-matrix theory.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Wikimedia CommonsDénes Gábor

(Budapest, 1900 – London, 1979) – Hungarian-British physicist and mechanical engineer

1971 Nobel Prize in Physics “for his invention and development of the holographic method”.

Parents: Bernát Günszberg and Adél Jakobovits.

Gábor began his studies in Markó Street Secondary School and then began studying engineering at the Royal Joseph University of Technology in 1918. He then continued his studies in Germany at the Technical College of Berlin.

It was the study of the basic processes of the oscillograph that led Gabor to investigate oscillographs and other electron-beam instruments such as electron microscopes and TV tubes. His research at the British Thomson-Houston Society focused on electron inputs and outputs, leading to the invention of holography in 1947. Holography was based on electron microscopy and thus used electrons instead of visible light. The earliest visual hologram was not achieved until 1964, following the invention of the laser, the first coherent light source, in 1960. Gábor became a British citizen in 1946 and spent most of his life in England. In 1948 he took up a post at Imperial College London, where he became a professor of applied physics in 1958 until his retirement in 1967. His rapid development of lasers and holographic applications in a wide range of fields (for example, art, information storage and pattern recognition) led to him being recognised worldwide.

He died in South Kensington, London in 1979.

Photo: nobelprize.org

Photo: nobelprize.orgGyörgy Oláh

(Budapest, 1927 – Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 2017) – Hungarian-American chemist

1994 Nobel Prize in Chemistry “for his contribution to carbocation chemistry”.

Parents: Gyula Oláh (Offenberger) and Magdolna Krasznai.

Oláh studied at the Piarist Secondary School in Budapest, going on to study organic chemistry at the Technical University of Budapest, where he earned a PhD in chemical engineering and taught organic chemistry from 1949 to 1954. Between 1954 and 1956, he was Head of the Department of Organic Chemistry and Co-Director of the Research Institute of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. In 1956, Oláh moved with his family to England and then to Canada, where he joined Dow Chemical in Sarnia, Ontario. His pioneering work on carbocationics began during his eight years there. In 1965, he returned to academia, becoming a lecturer at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. In 1971, he was granted United States citizenship. He then became a fellow at the University of Southern California, serving there as the Donald P. and Katherine B. Loker Professor of Chemistry from 1980. His research on stable, non-classical carbocations led to the discovery of protonated methane stabilised by superacids such as FSO3H-SbF5 (“magic acid”). Later in his career, his research on hydrocarbons and their conversion into fuels shifted to methanol production, namely, methanol from methane.

Oláh died in 2017 in Beverly Hills, California. In accordance with his will, he was laid to rest at the Fiumei Road Cemetery in Budapest.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Wikimedia CommonsJános Harsányi

(Budapest, 1920 – Berkeley, CA, USA, 2000) – Hungarian-American economist

1994 Nobel Prize in Economics shared with John Nash and Reinhard Selten “for their pioneering analysis of equilibria in the theory of non–cooperative games”.

Parents: Károly Harsányi and Alice Gombos.

Harsányi studied at the Fasori Lutheran Secondary School in Budapest. In 1939, he enrolled at the University of Lyon to study chemical engineering. However, the outbreak of the Second World War forced him to return to Hungary, and he graduated in pharmacy from the University of Budapest in 1944. Besides this, he pursued postgraduate studies in philosophy and sociology, obtaining a doctorate in both subjects in 1947. In 1948, Harsányi emigrated to Austria, and in 1950, to Australia. From 1956 to 1958, he studied at Stanford University on a scholarship, obtaining a PhD in economics and writing his dissertation on game theory. In 1964, he moved to Berkeley, California, where he taught until his retirement in 1990.

Harsányi is best known for his research on game theory and its applications in economics, in particular for his highly innovative analysis of incomplete information games, known as Bayesian games. He has made significant contributions to the use of game theory and economic reasoning in political and moral philosophy, in particular utilitarian ethics, and to the study of equilibrium selection.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons / Frankl Aliona

Photo: Wikimedia Commons / Frankl AlionaImre Kertész

(Budapest, 1929 – Budapest, 2016) – Hungarian author

2002 Nobel Prize in Literature “for writing that upholds the fragile experience of the individual against the barbaric arbitrariness of history”.

Parents: László Kertész and Aranka Jakab.

Kertész attended a boarding school and, in 1940, he started secondary school, where he was put into a special class for Jewish students. In 1944, at the age of 14, he was deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp, and was later sent to Buchenwald. After his camp was liberated in 1945, Kertész returned to Budapest and graduated from high school in 1948. Later he lived partly in Hungary and partly in Germany; it was in Germany that he received more active support from publishers and critics, as well as more appreciative readers. His best-known work, Fatelessness (Sorstalanság), describes the experiences of 15-year-old György Köves in the concentration camps of Auschwitz, Buchenwald and Zeitz. The novel and its sequels, Fiasco (1988) and Kaddis for an Unborn Child (1990), are Holocaust trilogies focusing on the horrors of the 20th century: hatred, genocide and the inhumanity that lies with the human soul. In 2009, Kertész was elected as a member of the Széchenyi Academy of Arts and Letters.

He is buried at the Fiumei Road Cemetery with his wife.

Fotó: Wikimedia Commons

Fotó: Wikimedia CommonsAvram Hershko (Ferenc Herskó)

(Karcag, 1937) –Hungarian-Israeli biochemist

2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry shared with Aaron Ciechanover and Irwin Rose “for the discovery of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation”.

Parents: Mosche Hershko (Mózes Herskó) and Shoshana Wulcz (Margit Wulcz).

Born into a Jewish family, Hershko, his brother and his mother were deported to a ghetto in Szolnok, from where most Jews were sent to Auschwitz, but he and his family managed to board a train that took them to a concentration camp in Austria. They survived the war and returned home. His father also returned, four years after they had last seen him.

Hershko and his family emigrated to Israel in 1950 and settled in Jerusalem. He received a medical degree in 1965 and a PhD in 1969 from the Hadassah Medical Center of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He is currently a distinguished professor at the Technion Rappaport Family Institute for Research in the Medical Sciences in Haifa.

Hershko and his colleagues pioneered the discovery of how cells regulate protein levels by tagging unwanted proteins with the polypeptide ubiquitin.

Photo: nobelprize.org

Photo: nobelprize.orgFerenc Krausz

(Mór, 1962) – Hungarian-Austrian physicist

2023 Nobel Prize in Physics shared with Pierre Agostini and Anne L’Huillier “for experimental methods that generate attosecond pulses of light for the study of electron dynamics in matter”.

Krausz graduated from Táncsics Secondary School in Mór. He studied theoretical physics at Eötvös Loránd University from 1981 to 1985, and then obtained a degree in electrical engineering at the Technical University of Budapest. In 1991, he obtained his doctorate at the Technical University of Vienna; it was there that he finished his habilitation in 1993 and served as an associate professor from 1996 and as a professor from 1999. In 2003, he was appointed Director of the Max Planck Institute for Quantum Optics in Garching, and in 2004, he became Head of the Department of Experimental Physics at the Ludwig Maximillian University of Munich.

Krausz’s research team was the first to produce and measure an attosecond pulse of light, using it to map the movement of electrons within atoms, laying the foundations for the science of attophysics, and, hence, the name “electron-sniping”. Femtosecond laser technology, which was the basis for attosecond measurement techniques, is now being used by Krausz and his team to further develop infrared spectroscopy for biomedical applications. Krausz is Head of the Center for Molecular Fingerprinting in Hungary.

Fotó: mta.hu / Szigeti Tamás

Fotó: mta.hu / Szigeti TamásKatalin Karikó

(Szolnok, 1955) – Hungarian-American biochemist

2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine shared with Drew Weissman “for their discoveries concerning nucleoside base modifications that enabled the development of effective mRNA vaccines against COVID–19”.

Parents: János Karikó and Zsuzsanna Göőz. Born in Szolnok, but she grew up and went to school in Kisújszállás. She got her undergraduate degree in biology in 1978, and a PhD in biochemistry in 1983, both from the Attila József University in Szeged. From 1978 to 1985, she continued her postdoctoral research at the Institute of Biophysics of the Szeged Biological Centre. She then left Hungary for the United States with her husband and two-year-old daughter. Between 1985 and 1988, she was a postdoctoral fellow at Temple University. She spent a year researching at Uniformed Services University and then at the University of Pennsylvania. In 2013, she became vice president of BioNTech RNA Pharmaceuticals. Her work laid the foundation for BioNTech and Moderna to create therapeutic mRNAs that do not cause inflammation. In 2020, Karikó and Weissman's technology was used in mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 manufactured by BioNTech and its partner Pfize, as well as Moderna. Since October 2021, Karikó has been a professor at the University of Szeged.

Karikó’s wide-ranging research underpins areas such as the creation of pluripotent stem cells, messenger RNA-based gene therapy, and a “new class” of drugs. Her main area of expertise is in ribonucleic acid (RNA)-mediated mechanisms, in particular in vitro-transcribed messenger RNA (mRNA) in protein replacement therapy. Karikó has laid the scientific foundations for mRNA vaccines, overcoming significant obstacles and scepticism within the scientific community.

One Unique Case:

The following Nobel Prize-winner was born in the Kingdom of Hungary as a Hungarian citizen of German parents; he changed his nationality when he was older and became a German citizen.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Wikimedia CommonsPhilipp E. A. von Lenard

(Pozsony, 1862 – Messelhausen, Germany, 1947) – Hungarian-German physicist

1905 Nobel Prize in Physics “for his work on cathode rays”.

Parents: Philipp Nerius von Lenardis and Antonie Baumann.

Born in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, von Lenard lived in Heidelberg, Germany. In 1907, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences changed Lénárd’s full membership to an honorary membership, which was open to non-Hungarian citizens. After completing his research in physics, he became politically active as a National Socialist, anti-Semite and a personal follower of Hitler.

He did not consider himself Hungarian.

Nobel Laureates of Hungarian Descent

The following Nobel Prize-winners had parents (ancestors) who were Hungarian but emigrated from Hungary; thus the following were not born in Hungary and their mother tongue and citizenship were not Hungarian. They were not educated in, nor did they work in Hungary. They are not (were not) members of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (John C. Polanyi is an exception).

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Wikimedia CommonsAlfred Fried

(Vienna, 1864 – Vienna, 1921) – Austrian writer, pacifist and Esperanto supporter

1911 Nobel Peace Prize (shared with Tobias Asser) “for his effort to expose and fight what he considers to be the main cause of war, namely, the anarchy in international relations”.

Parents: Samel Fried and Berta Engel.

Fried was born, lived, worked and died in Austria. He never visited Hungary and did not speak Hungarian.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Wikimedia CommonsRobert Bárány

(Vienna, 1876 – Uppsala, Sweden, 1936) – Austrian writer and otologist

1914 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine “for his work on the physiology and pathology of the vestibular apparatus”.

Parents: Ignaz Bárány and Marie Hock (Czech).

Bárány worked in Uppsala, Sweden for most of his life, died there, and was buried in Stockholm. He never visited Hungary and did not speak Hungarian.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Wikimedia CommonsRichard A. Zsigmondy

(Vienna, 1865 – Göttingen, Germany, 1929) – Austrian chemist

1925 Nobel Prize in Chemistry “for his demonstration of the heterogeneous nature of colloid solutions and for the methods he used, which have since become fundamental in modern colloid chemistry”.

Parents: Adolf Zsigmondy and Irma Szakmáry.

Zsigmondy studied in Austria, and later worked and died in Göttingen, Germany. He never visited Hungary and did not speak Hungarian.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Wikimedia CommonsMilton Friedman

(New York, NY, USA, 1912 – San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006) – American economist

1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences “for his achievements in the fields of consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and for his demonstration of the complexity of stabilization policy”.

Parents: Jenő Saul Friedman-Greenstein and Sarah Ethel Landau.

Friedman lived in the United States, and visited Hungary several times. He did not speak Hungarian.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Wikimedia CommonsCarleton D. Gajdusek

(Yonkers, NY, USA, 1923 – Tromsø, Norway, 2008) – American physician

1976 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine with Baruch S. Blumberg “for their discoveries concerning new mechanisms for the origin and dissemination of infectious diseases”.

Parents: Karol Gajdusek (Slovak) and Ottília Dobróczky.

Gajdusek lived in the United States, Australia, New Guinea and Norway. He visited Hungary several times. He did not speak Hungarian.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Wikimedia CommonsGeorge J. Stigler

(Renton, WA, USA, 1911 – Chicago, IL, USA, 1991) – American economist

1982 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences “for his seminal studies of industrial structures, functioning of markets and causes and effects of public regulation”.

Parents: Joseph Stigler (Bavarian) and Erzsébet Hungler.

Stigler lived in the United States, and never visited Hungary. He did not speak Hungarian.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Wikimedia CommonsElie Wiesel

(Sighet, Romania, 1928 – New York, NY, USA, 2016) – American writer and political activist

1986 Nobel Peace Prize “for being a messenger to mankind: his message is one of peace, atonement and dignity”.

Parents: Shlomo Elisha Wiesel and Sara Feig.

Wiesel lived in his hometown until 1944, when he and his family were deported to Buchenwald; in 1945, only he could be rescued. He then lived in France and then in the United States. He visited Hungary a few times, but did not speak Hungarian.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Photo: Wikimedia CommonsJohn C. Polanyi

(Berlin, 1929) – Canadian chemist

1986 Nobel Prize in Chemistry shared with Dudley R. Herschbach and Yuan T. Lee) “for their contributions concerning the dynamics of chemical elementary processes”.

Parents: Mihály Polányi and Magda Kemény.

Polányi lives in Canada and is a retired professor at the University of Toronto. He was elected as an honorary member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in 2001. He has visited Hungary twice, but does not speak Hungarian.

Photo: nobelprize.org

Photo: nobelprize.orgH. David Politzer

(New York, NY, USA, 1949) – American theoretical physicist

2004 Nobel Prize in Physics with David Gross and Frank Wilczek “for the discovery of asymptotic freedom in the theory of the strong interaction”.

Parents: Aladár Politzer and Valerie Diamant (Tamar).

Politzer lives in the United States and is a professor of physics at CalTech Pasadena. He has never visited Hungary and does not speak Hungarian.

Fotó: Gasper Tringale

Fotó: Gasper TringaleLouise Glück

(New York, NY, USA, 1943 – Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023) – American poet

2020 Nobel Prize in Literature “for her unmistakable poetic voice that with austere beauty makes individual existence universal”.

Her paternal grandparents – Heinrich Glück and Terese Moscowitz – were Hungarians from Érmihályfalva.

She lived in the United States, and never visited Hungary. She did not speak Hungarian.